How I uncovered Victoria's secret love: Historian Fern Riddell explains all

There have long been whispers of a romance between the queen and her Scottish servant John Brown, but nothing concrete to support them. Now Fern Riddell, author of an explosive new book, reveals how she turned sleuth to track down evidence of their secret passion

The story that’s consumed my life for much of the past few years has it all: family dysfunction, political intrigue, royalty, the rewriting of our national history. A secret hidden for generations. These are the sort of things historians can get carried away by.

When we’re undertaking historical research, it often becomes clear that the relationship between fact and fiction can be a murky one. There’s often a gap between what we want the truth to be and the reality of the lives that have been lived. So it was with my latest project. After four months of research, I couldn’t quite believe what I’d uncovered.

I’d been tracing the footsteps of both historians and historical people, and I was finally convinced that what I’d found came close to representing irrefutable proof of a remarkable secret – one offering an answer to a 160-year-old question. But making the breakthrough didn’t come without risk – one faced by nearly every historian who had got so far before me, and who turned back at the final hurdle, unable to bring their research to light.

WATCH | Fern Riddell on her quest to discover the secrets of Victoria's later love life

So, before I pushed ahead, I called a trusted friend and mentor to discuss what I thought I’d discovered. “I’ve found it,” I exclaimed. “I’ve found the lost archive of Queen Victoria and John Brown.”

Royal inspiration

Towards the end of 2021, my agent, Kirsty McLachlan, had set me a challenge.

“You need a new project,” she declared. “What can you say about Queen Victoria?”

“I don’t do the royals,” I retorted, instantly rejecting the suggestion. “Anyway, most royal historians face censorship the moment they find anything interesting.”

My focus has always been on the stories of ordinary people – what we call ‘history from below’. These are the lives that fascinate me, not those of the wealthy and powerful. Victoria felt like a lost cause. After all, what could be left to discover about one of history’s most famous women?

But there has always been something fascinating about Queen Victoria. She is an enigma: a woman who became the cornerstone of an empire, a queen, a wife, a mother and an icon of an entire age. Her life with her husband, Prince Albert, has been the subject of multiple dramas and documentaries, as has her grief-stricken widowhood after his death in 1861, aged only 42. But what this passionate mother of nine did for her own comfort in the lonely decades that followed has only been whispered about, until now. There have long been rumours surrounding Queen Victoria’s relationship with her Scottish Highland servant, John Brown. Were they lovers? Did they marry in secret? Did they even have a child together? However, no one had been able to establish the truth. This, I decided, was something that piqued my curiosity – a thread to pull and see where it led.

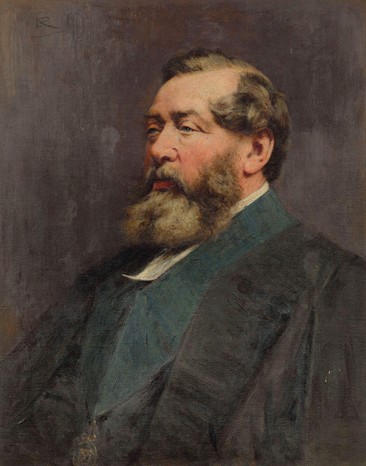

John Brown is often relegated to a footnote in Victoria’s history, glossed over as a servant, or awkwardly portrayed as ‘just a friend’. Yet for almost 20 years he stood at Victoria’s side as her “strong right arm”, her “best friend” – and, as I discovered, her “beloved John” and her “true and devoted one”. But as I carefully set out on my research, I had little comprehension of the journey I was about to take, nor the astonishing secret it would reveal.

- Read more | “There was a general perception that Queen Victoria’s mourning was neither normal nor acceptable”

Searching for sources

With the thought of perhaps writing about Victoria’s mid-life, I ordered every book ever written about John Brown. Modern historians have long believed this to be a pointless effort, knowing that most of John’s original documents – his diaries, letters and more – were destroyed by members of Victoria’s court after his death in 1883. But I felt sure that something must remain somewhere.

I started with Queen Victoria’s John Brown by EEP Tisdall, which was published in 1938. It’s gossipy and fun, but entirely devoid of references or sources – useless for my purposes, except for insights into how John was seen 50 years after his death. Next up was Tom Cullen’s The Empress Brown: The Story of a Royal Friendship, released some three decades later. This turned out to be a goldmine. In its pages are a series of letter facsimiles from Victoria, the original documents faithfully reproduced for readers.

Historians believed that Brown's diaries and letters were destroyed by Victoria's court

They showcase such a tenderness between Victoria and John, as well as his family, and I felt an itch – a historian’s twitch – that there was much more to this history than I had been aware of before. While combing Cullen’s acknowledgements, I saw a reference to John’s descendants, and a brief mention that they held a family archive. This is also hinted at by Raymond Lamont-Brown, author of John Brown: Queen Victoria’s Highland Servant (2000).

That was when things started to become interesting. Although rumours of a family archive, kept safe by John’s surviving relatives, have long swirled, no one would say where it was held or if it still existed.

This felt like a mystery I wanted to solve. These letters must be real, I thought – more than one person claimed to have seen them – yet only Cullen provided evidence. No historian since had been able to bring them into the public eye. Had they been destroyed? Lost? Or were they still out there, waiting to be found?

I started by tracing John’s surviving family: the descendants of his brothers James, Donald, William, Hugh and Archie. Hugh and Hilda Lamond, grandchildren of John’s second-youngest brother Hugh, appear in historians’ acknowledgements more than once, and I became convinced that they must have been the guardians of the family archive. But their own descendants emigrated to the US in the 1970s, and I had no idea how to contact them.

I reminded myself that modern historians need to be able to utilise many different tools and skill sets for our research. One of the most powerful resources we have today is the internet, providing access to digitised records. In the space of a single afternoon, using the gigantic global databases available via Ancestry and Scotland’s People, I mapped out John Brown’s entire family – including his brothers and cousins – through births, marriages, deaths and census records. This led me to Minnesota, and a burning question: did John Brown’s great-great-great-nieces still hold on to their family’s precious collection, packed carefully in moving crates, carried down the generations and now possibly on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean?

Long shot

At that point, the pandemic continued to hold the world in its grip. How was I to get in touch with Brown’s relatives some 4,000 miles away in the US? Genealogy can get you only so far, and I had no up-to-date contact information. And yet… might they be on Facebook? It seemed like the longest of shots but, as I typed their names into the search bar, a result flashed up instantly. A connection to the descendants of Hugh Brown – the only people who might, just possibly, hold the keys to the John Brown family archive – was right in front of me. I opened up Facebook’s messenger app and began to type, unsure if I would get a response. Eventually I hit send – and sat back to wait.

Days and weeks went by, with no response from Minnesota. So I returned to the documents I could access – those letters uncovered by Cullen more than 50 years ago – for hints that some of John Brown’s papers must have survived somewhere. On a whim, I typed lines from the letters into Google – and, to my shock, a link to an archive in Aberdeen appeared. Suddenly, there it was in high definition, staring back at me: an original letter, kept safe by Aberdeen City Archives.

As I gazed at the screen, the realisation slowly dawned on me that I could confirm for the first time the existence of part of the John Brown family archive. Surely it couldn’t be simply sitting there, waiting to be discovered? But I learned a long time ago that, with a history and a nation as diverse as ours, and with correspondingly bulging archives, answers are often to be found sitting in plain sight.

Within an hour I found two more letters in the archives, digitised and perfunctorily labelled. There was nothing to give away their significance, no indication of their importance. But if I could confirm that at least some of the archive had survived, then might that prove there was more out there to find? And why, after John Brown’s family had kept this secret for so long, was some of it now available in a public archive with little information and no fanfare?

I booked a research trip to Aberdeen. Meanwhile, I began the forensic work of raking through the city’s entire online library, collections and archives. I realised that references to John Brown, both artefacts and letters, are scattered across Aberdeen’s new Treasure Hub, Aberdeen Art Gallery and Town House archive. On my first research trip to the city, I held the original letters in my hands, reading in Victoria’s own handwriting her memories of John: “So often I told him no one loved him more than I did… and he answered, ‘nor you than me, no-one loves you more’.” I was awestruck by this powerful declaration between Victoria and John.

In Town House, the team allowed me to rifle through the collection of the writer, artist and historian Fenton Wyness. I’d found a passing reference that this included some material on Brown, but what I found there astonished me. At some point in the 1950s or 1960s, Wyness – a local Aberdeenshire historian – decided to write about John Brown. Like Tom Cullen, he was given access to the John Brown family archive, which he then proceeded to photograph in its entirety. Now, in the archive in Aberdeen, I realised that a record of the letters, documents, cards and gifts from Victoria to John and his family was sitting in boxes all around me. It’s an incredible resource to study – a reference collection that is utterly unmatched.

Pieces of the puzzle

Over the three years that followed, as I travelled to Aberdeen and to other archives and private collections across the country, Victoria and John’s life together began to unfold. And the story is vastly different to the one we have been told before – as I reveal in my new book, Victoria’s Secret: The Private Passion of a Queen. The documents I unearthed and studied provide undeniable proof of an intense love affair and, I believe, evidence that John Brown and Victoria did indeed marry – as well as of a determined and ongoing campaign to eradicate him from her history after their deaths.

The language Victoria used in her letters to describe her relationship with John deepened as the years went by. She called him her “darling one”, “faithful and devoted”, while describing herself as his “true and devoted one”. Cards she sent him, recorded in the John Brown family archive, are printed with the words “I have loved thee with an everlasting love” and poems such as “I send my sewing maiden / with new year’s letter laden, / its words will prove / my faith and love, / to you my heart’s best treasure, / then smile on her and smile on me, / and let your answer loving be / and give me pleasure.”

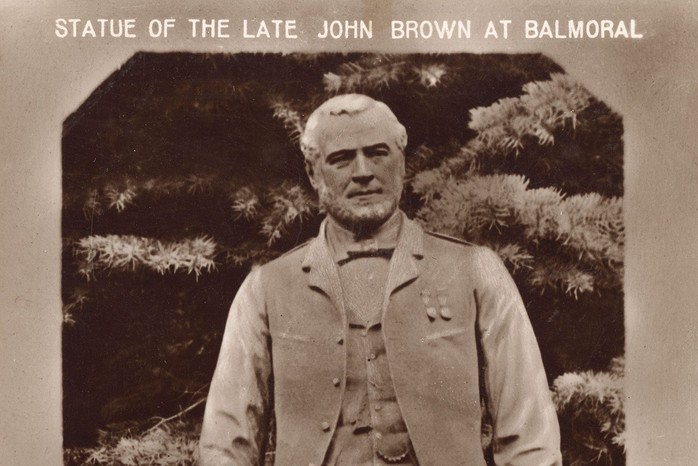

Also revealed in Victoria’s Secret is the possibility that Victoria and John had an ‘irregular marriage’, a legal marriage under Scottish law that involved an exchange of vows and potentially rings, the evidence of which sits in portraits and photographs of John from 1873 onwards.

Add to this the fact that Victoria’s Scottish chaplain, Norman Macleod, confessed on his deathbed to marrying them, and that Victoria went to her grave wearing John’s mother’s wedding ring – a point that was hidden from her children at the time – and it feels to me like solid, irrefutable evidence of their relationship.

Floored by photos

Although I tried to remain clinical and dispassionate as I weighed the material that I was collecting, a couple of objects floored me. In Treasure Hub sits a photographic album Victoria dedicated and gifted to John’s mother, Margaret Leys. It is bursting with pictures of both Brown’s family and her own, side by side – a record of all of the people who mattered to them.

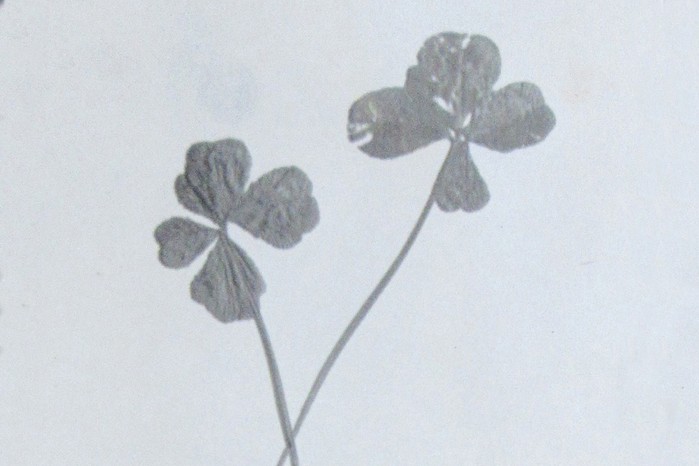

But nothing prepared me for the revelation that, in the week after John’s death, Victoria had his hand cast and then carved in stone. The photograph of this object in Fenton Wyness’s collection – the tender placement of John’s hand on a pillow, the importance given to a signet ring that he wore every day from 1873 onwards – felt like a gut punch. Finally, there is a pair of four-leafed clovers that Victoria and John collected, and which he dried and taped into a scrapbook, their stems crossed over one another for eternity. In the Victorian language of flowers, this has a singular meaning: Be Mine.

I still had unanswered questions, though – and the only people who might have been able to help answer them were thousands of miles away in America. Fortunately, at that stage Angela, one of Hugh Brown’s descendants whom I’d attempted to contact via Facebook, got in touch. She is bubbly and forthright – and, with the agreement of her family, was happy to discuss their history and the stories she had heard while growing up.

Over a series of calls, emails and texts, she slowly began to trust me with a secret her family had kept for a very long time. Not only do they have the final remnants of the John Brown family archive, including original documents, such as Victoria’s own investigation into John’s family history, but they also guard a story that is fantastical and amazing. Angela was sanguine, telling me that “it’s just what I’ve always been told – I don’t know if it’s true”. Even so, I couldn’t help but wonder: could this be the final missing piece of the puzzle for which I’d been searching so long?

Throughout my research, and across John’s life, one of his siblings featured more prominently than all of the others: Hugh, whose family became the guardians of John and Victoria’s legacy. As I was writing and researching, it became increasingly clear that, though all of John’s brothers and their families mattered to Victoria, Hugh and his wife, Jessie, were most dear to the queen. Unusually among John’s extensive clan, they had only one child – a daughter, Mary Ann, Angela’s great-grandmother. According to Angela, Mary Ann was the secret child of John Brown and Queen Victoria.

Whispers of a love child have swirled since the 1860s, but historians have always been quick to dismiss such rumours. They claim that Victoria was unable to have more children after the birth of her last acknowledged daughter, Princess Beatrice, in 1857, as she suffered from a prolapsed uterus. However, this condition was only discovered after the queen’s death in 1901. None of Victoria’s doctors reported any evidence that she suffered it in the aftermath of Beatrice’s birth. As a prolapsed uterus is common – nearly half of women over 50 will experience some form of pelvic organ prolapse during their lifetime – I believe this ‘fact’ has become historical misinformation, used to discredit any chance of a child between Victoria and John.

Moreover, as I discovered during my research, although Victoria was advised not to have more children after Beatrice, it had no connection to her physical health. After her repeated battles with severe post-partum depression, including hallucinations and possibly even psychosis, Victoria’s doctors were terrified that another pregnancy would send her mad. This was the reason why she was advised against having any further children. But there is even evidence to suggest that she was planning to have another baby before Prince Albert died in 1861.

Victoria’s doctors were terrified that another pregnancy would send her mad

“Mama so longed for another child,” her eldest daughter, ‘Vicky’ (Victoria), wrote after Albert’s death. So it is perfectly possible that Victoria could have had a child with John in 1865, the year of Mary Ann’s birth. The queen was healthy, fertile and only 45. Many of John’s female relatives – indeed, Victorian women more generally – had children into their mid- to late forties.

Journey of discovery

It was not the end of the story, of course. But that discovery set me on a long journey to try to separate family memory from historical fact. My research took me from the glorious glens of the Scottish Highlands to the wildness of 1860s Otago in New Zealand’s South Island, and back again. The reality of Victoria’s secret was long buried by panicking politicians, government campaigns, cowardly courtiers and family rebellion. Without DNA evidence, we may never know the truth – but, every time I speak to Angela, I find myself surreptitiously looking for any resemblance to Victoria in her face.

The revelation that the queen chose the son of a Scottish crofter as her second husband, and potentially had a child with him, would have rocked Victorian society like a nuclear explosion. Her world did not believe that a common man could look at a king as an equal, let alone marry a queen. Yet, based on the evidence I’ve found, I believe that this is exactly what Victoria did. Far from remaining the grieving widow for the rest of her days, she spent her passionate mid-life privately joined to a man who saw her as “his only object in life”. Now it is time for John and his family to take their rightful place in history once again.

Dr Fern Riddell’s new book, Victoria’s Secret (Ebury Press), is out now in hardback. The book has inspired a Channel 4 documentary, Queen Victoria: Secret Marriage, Secret Child?, which is available to stream now

This article is in the September 2025 issue of BBC History Magazine